Welcome To My Blog!

A pine tree is a cone. -/-/-/

Clinging and swinging and hanging up high. /--/--/--/

Sealed like a secret and ready to fly. /--/--/--/

The wind starts to blow, Then look out below! -/--/-/--/

A pine tree begins with a cone. -/--/--/

A pine tree is a sapling. -/-/-/-

Stretching and reaching for sunlight and rain, /--/--/--/

Watching the seasons pass once, twice, again. /--/--/--/

Root digging down, Her branches a crown, /--/-/--/

A pine tree turns into a sapling. -/--/--/-

A pine tree is a tower. -/-/-/-

Covered in needles, bristly and lean. /--/-/--/

Steady, unchanging, a coat evergreen. /--/--/--/

Patiently growing, Trusting and knowing /--/-/--/-

Someday, she’ll be a tall tower. /--/--/-

THE PINE CONE’S SECRET

A Life Cycle Poem

Words by Hannah Barnaby

Pictures by Cedric Abt

I have scanned this as dactylic/tetrameter done in quatrains. This is a concept book.

There is so much to say about this poem, however because space limits me, I will focus on something less talked about and that is mixed meter.

What is mixed meter?

-

Mixed meter is not metrical variation.

-

Mixed meter is the addition or substitution of the base meter.

Why use mixed meter?

-

To avoid predictability and to keep the listener engaged.

Is mixed meter allowed?

YES! However, there must be a reason for the switch-up. And once you decide to use mixed meter the pattern must remain consistent throughout your manuscript.

-

Can you identify where this author has used mixed meter?

-

Can you understand the reason?

I will give you a hint. The mixed meter is in the first line of every stanza. This first line serves as a topical sentence. This introduces you to the purpose of the stanza. This book goes on to relate how a pine cone circles back to a pine tree.

Click for my YouTube video

Once inside a chicken’s nest. /-/-/-/

A dozen eggs, all grade-a-best, -/-/-/-/

lay still and warm, the contents sleeping, -/-/-/-/-

all but one… who came out peeping. /-/-/-/-

This sunny chicken loved to cheer, -/-/-/-/

though frown-ups groaned when she came near. -/-/-/-/

“She needs to understand we’re busy, -/-/-/-/-

And her cheering makes us dizzy.” /-/-/-/-

CHEERFUL CHICK

By Martha Brockenbrough

Illustrated by Brian Won

I have scanned this as iambic/tetrameter done in quatrains.

Iambic is an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable. Similar to da DUM.

Why did I scan this as iambic and trochaic? In truth it could be either one.

What needs to be done when scanning poetry is to try and find the base meter. That means the metrical pattern that is most consistent.

In the first stanza we have two trochaic meters and two iambic meters. So far, we are head-to-head. On to the next stanza. There we count three iambic meters and one trochaic meters. So, iambic wins! However, the important point NOT to be dismissed is that the hard beasts remain consistent.

Another interesting technique this author has used is the enjambment. The second line flows to the third line, to the fourth line.

With all this flowing from one line to the next, did you happen to notice the ellipsis? Were you not jarred by this as I was, in a pleasant way?

I loved this story poem about a cheerful chick who lived among a barnyard of grumpy animals.

Click for my YouTube video

There’s a slumbering hush in the barn on the hill. --/--/--/--/

As the stars twinkle down, all is calm, all is still. --/--/--/--/

No mooing, no neighing, no oinking, no quacking. -/--/--/--/-

Just the rumbling snores. . . --/--/

And the faint sound of . . . --/--

CLACKING! /-

. . .it’s Mavis the chicken, click-clacking her KNITTING! -/--/--/--/-

“I’m a bird,” Mavis sighed, “who finds EVERYTHING scary. --/--/--/--/-

MAVIS THE BRAVEST

Written by Lu Fraser

Illustrated by Sarah Warburton

Perhaps you have heard that picture book writers are told NOT to rhyme.

Agreed there are a few daunting challenges to overcome. Challenges like is the story serving the rhyme or is the rhyme serving the story. Are we losing the plot, tension and character arc in the process?

Do not lose heart for this can be overcome.

Here are the W questions every story needs to ask. Who is the main character? Where is the story taking place? What does the main character want? Why does the main character want this? Let’s see how these questions are answered with this story.

-

Who-Mavis

-

Where- Barn

-

Wants- Wants to be brave.

-

Why- So she can stop knitting and go to sleep.

We are introduced to a chicken who is chicken. We learn her solution to distract herself is to knit. All within the first few spreads.

And we want to know how it will turn out for her, so we turn the page.

So, in the spirit of Mavis, I say forge ahead! Make your character memorable, dimensional and give them a quirk. Answer all the W questions in the first few paragraphs. And last of all study rhyming story books and learn how this is done.

Does the intro sound a teeny bit like Click clack Moo? Yeah, maybe, sort of, but the story line is different. It is hilarious and delightful and not a copy at all!

Written by Tim McCanna

Illustrated by Ramona Kaulitzki

Cold is a morning /--/-

dappled in dew, /--/

a canvas of sky painted yellow and blue. -/--/--/--/

Over a mountain /--/-

misty and gray, /--/

a hawk braves the chill of a midwinter’s day. -/--/--/--/

Cold is a river /--/-

rushing on stone, /--/

the slow, steady beat of its murmuring drone. -/--/--/--/

The metaphor is a simple comparison of two non-similar things. A metaphor can take you beyond the literal meaning of the word.

Extended Metaphors are metaphors that get continued or drawn out across successive lines in a paragraph or verse.

-

Did you notice how use the metaphor spanned multiple paragraphs?

-

Did you notice how it added detail to the original comparison.

-

Did you notice how this comparison became a more developed way to express an idea or emotion.

Why use the metaphor?

-

It contributes to a bigger picture.

-

It leaves you wanting more.

-

It can linger with you long after the page is put down.

EXAMPLE: THE ENJAMBMENT

Velvety soft are the sweaters you wear. /--/--/--/

Tingly and cool is the fresh autumn air. /--/--/--/

Crinkly and crisp are the leaves on the ground /--/--/--/

as you crunch up the piles that have swirled in a mound. --/--/--/--/

Fuzzy and spiked are the stiff thistle weeds. /--/--/-/

Feathered and fluffy are slim, long-stemmed reeds. /--/--/--/

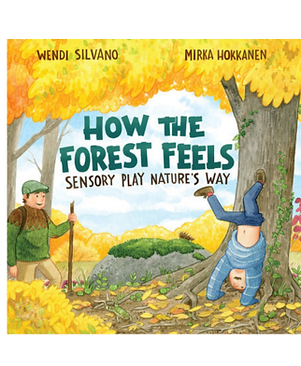

HOW THE FOREST FEELS Sensory Play Nature’s Way

Wendi Silvano

Mirka Hokkanen

I have scanned this story poem as headless anapestic/tetrameter done in couplets.

There are a few multisyllabic words that I’ve scanned as a soft beat. I have done this because that is how it flows when I read it out loud. Scroll down on my blog and you will see the reason for this. Anyway, read it out loud for yourself and then you decide. Did you trip over the last line? Yeah, I did too, a little bit. But, I could make an argument that these last words in the stanza qualify as spondees. Therefore this book goes in my recommended reads for this blog post.

This is best described as a mood piece. But for this blog post I will focus on the enjambment used.

-

What is an enjambment?

Enjambment is the continuation of a sentence or clause across a line break.

Enjambment, from the French meaning “a striding over,” is a poetic term for the continuation of a sentence or phrase from one line of poetry to the next.

-

Why use enjambment?

To speed up the pace of the poem or to create a sense of urgency, tension, or rising emotion as the reader is pulled from one line to the next.

In the case of this book the author used enjambment to surprise. With each line we expect the sentence to end. When it carries over to the next it becomes refreshing, engaging and we want more.

This book is beautiful to the very end!

EXAMPLE: REPETITION

In a garden on a hill /-/-/-/

sparrows chirp and crickets trill. /-/-/-/

In the earth a single seed /-/-/-/

sits beside a millipede. /-/-/-/

Worms and termites dig and toil /-/-/-/

moving through the garden soil. /-/-/-/

Then at last a tiny shoot /-/-/-/

ever slowly forms a root. /-/-/-/

First a seedling then a sprout /-/-/-/

pushing bursting up and out. /-/-/-/

In a garden day by day /-/-/-/

newborn flowers find their way. /-/-/-/

IN A GARDEN

By Tim McCanna

Art by Aimee’ Sicuro

Repetition is a literary device that involves intentionally using a word or phrase for effect, two or more times in a speech or written work. You will have to read the entire book to see how effectively the author used this technique.

-

In this poem the image is created.

-

First, we are introduced to a garden on a hill.

-

From there we see a garden begin to emerge.

-

Through repetition a mood is communicated.

-

Repetition helps poets communicate specific tones.

-

Feelings and experiences are emphasized.

-

Meaning accrues.

-

Expectations are created.

We look at all the things from different angles.

I have found this book to be one of the most beautifully written I’ve read, intoxicating even.

The night is for darkness. -/--/-

And bright golden beams. --/-/

For discovering eyes --/--/

are not what they seem. -/--/

The night is we're running -/--/-

Barefoot and fast, /--/

through sweet Meadow Flowers --/-/-

And tall Dewey grass. --/-/

WORLD OF WONDER

THE DEEP BLUE

THE NIGHT IS FOR DARKNESS.

By charlotte Guillain

Illustrated by Lou Baker Smith

This is the first poem in a poetry collection.

Is there a place for slant rhyme in poetry?

Yes! In blank verse! So what is blank verse?

Blank verse is metered but without the need for the end rhyme. This frees up the writer to say what they want to say. No need to go looking for a rhyme. No sentence inversions. No frustrations.

Often slant rhymes are used and sometimes an end rhyme is thrown in. Either way it has a musical quality.

This poetry collection allows the child to recognize a patterns. When brains are enjoyably engaged, learning becomes an pleasurable process.

-

Did you notice the slant rhymes?

-

The first sentence states the topic.

-

The following sentences describe this topic.

This is sooo beautiful!

EXAMPLE: PERSONIFICATION

Empty sidewalks doze. /-/-/

Tree boughs gently sway. /-/-/

Main street blinks awake, /-/-/

Quiet, still and gray. /-/-/

Soft light slowly spreads, /-/-/

Bin by sleepy bin. /-/-/

Flag scoots up the pole, /-/-/

Produce van pulls in. /-/-/

Lamppost stands up straight. /-/-/

Shadows slip away. /-/-/

Curtains peek outside. /-/-/

Shop clerk starts his day. /-/-/

GOOD MORNING MAIN STREET

Words by Catherine Bailey

Art by Fiona Lee

Personification is where an idea or thing is given human attributes and/or feelings.

Personification allows writers to create life and motion within inanimate objects, animals, and even abstract ideas by assigning them recognizable human behaviors and emotions.

Why use personification?

-

To elevate your writing

-

To add emotional depth

Create Your Own Personification

-

Pick an object or idea around you (like the sun, your phone, or even time).

-

Write down a sentence where you give it human qualities

Have you ever come across a book that you wished you had written? This is one of them and this is gorgeous writing. Go get it and find out for yourself.

EXAMPLE: REPETITION

They said I could’nt change the world -/-/-/-/

It wasn’t worth the fight. -/-/-/

But in my head, a small voice said. . . -/-/-/-/

Maybe you might. /-/ /

There was nothing green or growing /-/-/-/-

In the country of my birth: /-/-/-/

The very hottest, driest place -/-/-/-/

On all this, hot dry earth. -/-/-/

MAYBE YOU MIGHT

By Imogene Foxell

Art by Anna Cunha

Repetition reuses words, phrases, images, or thoughts multiple times.

This could be a theme, a character’s characteristics, or the terrible, or wonderful, state of the world. In this way meaning accrues through repetition. In this story poem the thought is repeated in different ways.

It can be used in any part of the poem. It does not have to be limited to the ending or beginning.

Repetition is a way to produce deeper levels of emphasis, clarity, and amplification.

If you want to write a poem with repetition, first think about the point you want to get across. Then experiment on how you can incorporate a repeated word, phrase, line, or stanza into your poem.

EXAMPLE: FREE VERSE

Awaken to the calm-

the peaceful pink of dawn’s night.

Note a kiss of air, a soft breath,

a phantom wisp, faint as shadows,

cool and crisp.

Bend an ear to the breeze-

hear the scuffling, ruffling futter-

leaves go scuttling in the gutter.

See the shifting grasses shudder-

Sharing whispered summer secrets

With the silent, stalking egrets.

Hear the wind blow

By Doe Boyle

Illustrated by Emily Paik

Free verse can be defined as poetry that is free from limitations of regular meter and rhyme. A free verse poem provides artistic expression, in that it closely follows the cadences of human speech.

By using techniques such as metaphor, simile, alliteration, consonance, assonance, the writer of free verse does not just provide information, but also stirs emotion.

The peaceful pink of dawn’s night. Can you not see the sun set?

Note a kiss of air, a soft breath. Can you not smell the freshness in the forming dew?

A phantom wisp, faint as shadows. Can you not feel the breeze on your cheeks?

This picture book focuses on how the wind affects our world. Each stanza represents one of the thirteen categories of the Beaufort wind force scale.

Why not give it a try? Close your eyes, stir you senses and write what you feel.

Written by Ed Shankman

Pictures by Dave O’Neill

The desert’s a place full of wide-open space – -/--/--/--/--

which is great for a hike, or a game, or a race. --/--/--/--/

So most desert friends spend their time having fun, --/--/--/--

living life on the run in the bright desert sun. -/--/--/--/

There are cougars, coyotes, and jackrabbits, too. --/--/--/--/

And the badgers and porcupines show up on cue. --/--/--/--/

Then the prairie dog crew simply pops into view. --/--/--/--/

And together they always find something to do. --/--/--/--/

Anapest is a metrical foot wherein the first two syllables are short and unstressed, followed by a third syllable that is long and stressed. da-da-DUM

Since anapest ends in a stressed syllable, it has a singsong rolling feel to it. It drums a beat like music and is popular in stories for children.

It is also a poetic device used to express long lines with fluidity.

-

Did you notice the length of the lines in this story book?

One more thing to note. I have chosen to scan multi syllables as if they were one. The weight of my argument is; you must know the rules first, before you can break them. This placing of beats comes from reading it out loud. Poetry is meant to be read, embraced and measured out loud.

Language will vary according to where you live. For example: sometimes words are slurred, sometimes words run together, or sometimes they collide. I could not find a proper counterargument as to where these beats should otherwise land.

Go ahead and read the above portion to yourself, out loud. Then you decide.

EXAMPLE: DACTYLIC METER

This is the forest. /--/-

This is the steeple. /--/-

Giants and saplings /--/-

and just a few people. -/--/-

Follow the creek. /--/

Glide where it bends. /--/

High-five the ferns. /--/

Hello, friendly friends! /--/

This is a redwood. /--/-

Look how it soars, /--/

surrounded by sorel -/--/-

crowding the floor. /--/

Written by Meg Fleming

Illustrated by Chick Groenink

A dactyl is a metrical foot of a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables. The word dactyl comes from the Greek word daktylos which means “finger.”

Why would you want to use a dactyl in your writing?

Dactylic syllables give a punchy impactful effect and mood of a poem.

So how has this author achieved this?

-

Did you notice the emphasis on the word “this” at the beginning of the line?

-

Did it not arouse your attention?

-

Did it not create expectations of what wonders will follow?

Regarding why I decided to make a multi-syllable word as one beat, well, you’ll have to look for the answer in another post.

This book is so beautiful it stands as one of my top five all-time favorites.

EXAMPLE: CUMULATIVE STORY STRUCTURE

This is my piano.

Inside is the frame -/--/

enclosed in this case, -/--/

that lies on these legs -/--/

with wheels at their base, -/--/

to pillar and prop my piano. -/--/--/-

These are the pedals /--/-

pressed down to the ground, -/--/

under the soundboard -/--/-

where bridges are bound, -/--/

Written by Jen Fier Jasinski

Illustrated by Anita Bagdi

A cumulative story starts with an opening sentence.

From there details are added, the narrative builds by repeating what’s to come.

A cumulative story can rhyme but does not have to.

Why is a cumulative story so wonderful?

-

It is invaluable for emerging readers.

-

It gives them confidence by predicting what comes next.

-

Children who aren’t reading yet will be able to guess the outcome and get it right!

This story adds nonfiction elements. Be sure to check out the glossary!

With a cumulative story reading becomes fun and learning and engaging.

EXAMPLE: THE COUPLET

There is a special place for books, -/-/-/-/

A place they live in shelves and nooks. -/-/-/-/

From A to Z stacked high in piles -/-/-/-/

These books go on for miles and miles. . . -/-/-/-/

So come inside and take a look -/-/-/-/

It’s time to find your favorite book! -/-/-/--/

Too many books to pick just one. . . -/-/-/-/

The trick is choosing-that’s the fun! -/-/-/-/

THE LIBRARY BOOK

By Gabby Dawnway

Illustrated by Ian Morris

A couplet features two consecutive lines of poetry that typically rhyme and have the same meter. A couplet can be part of a poem or a poem on its own.

By distilling the main ideas of the poem into brief two-line units, the poet creates more of an impact.

Emotion, and tone all must be condensed, making each word choice count.

-

Did you notice the light stepped pace with these couplets?

-

Did you notice the playful tone, as if tiptoeing into a room?

-

Did you notice how both lines complete the one thought?

-

Did you notice the image each couplet has created?

EXAMPLE: REPETITION

This is the farm, /--/

land that she loves. /--/

These are the keys, /--/

hidden way out of reach. -/--/

Latches clank open, /--/-

and shed doors. . . screeeeech! -/--/

This is the combine, /--/-

enormous and red. -/--/

Grumbling and growling, /--/-

it creeps from the shed. -/--/

IT’S CORN PICKING TIME

Written by Jill Esbaum

Pictures by Melissa Crowton

This poem is done in dactylic or anapest diameter.

I have scanned some words with two syllables as one syllable. Poetry is meant to be read out loud. The ears pick up what the silent mind does not. Beats play like music. They can be booms, plinks, bongs, tweaks or twinges. Sometimes words are slurred, sometimes words run together, or sometimes words collide precipitately. Go ahead and read the above portion to yourself. Then you decide.

Now on to repetition.

Repetition is a literary device that involves intentionally reusing a word or phrase. You will have to read the entire book to see how effectively the author used this technique.

-

The farm image is created.

-

Feelings and experiences are emphasized.

-

Meaning accrues.

-

Expectations are created.

-

We look at farm life from different angles.

Through that idea’s juxtaposition, the idea becomes multifaceted. The poem’s repetition and concision or preciseness become clearer over time.

This book introduces us to the sights, sounds and smells of corn picking time.

Delightful!

EXAMPLE: METONYMY

Neigh-a-bye lullaby /-/

Slowly swaying rock – a – bye /-/-/-/

Nuzzle nose, breathing deep /-/ /-/

Plodding, nodding off to sleep /-/-/-/

Moo-a-bye lullaby /-/

Droop eyelids flutter – sigh //-/-/

Setting in, hoof to chin /-/ /-/

Milky dreams come floating in /-/-/-/

FARM LULLABY

By Karen Jameson

Art by Wednesday Kirwan

What is metonymy?

Metonymy is a type of figurative language in which an object or concept is referred to not by its own name, but instead by the name of something closely associated with it.

-

The use of metonymy dates back to ancient Greece.

-

Metonymy is found in poetry, prose, and everyday speech.

-

A common form of metonymy uses a place to stand in for an institution, industry, or person.

-

Metonymy in literature often substitutes a concrete image for an abstract concept.

Did you notice how this was done? For example: Neigh-a-bye lullaby and Moo-a-bye lullaby?

Is this not a fun filled read-a-loud?

When the night sky is high like a ceiling of stars, --/--/--/--/

I look up at the face of the moon. --/--/--/

What do you see, I ask, there where you are? /--/--/--/

And the moon says, right now, I see you. --/--/--/

I count the bright hundreds of waves on the sea -/--/--/--/

as they crash and they rush to the shore. --/--/--/

And I let those waves touch their cold hands to my feet. --/--/--/--/

Roar, say the waves, so I roar. /--/--/

And I look at the flowers that grow in the field --/--/--/--/

as they turn their heads up to the sky. --/--/--/

So I turn my head too, just to feel what they feel --/--/--/--/

with the sun and the wind blowing by. --/--/--/

By M.H. Clark

Illustrated by Laura Carlin

The galloping rhythm of anapests can give poems a joyful and buoyant feeling. The use of the anapest is ideal for children's stories.

Compared with the heart-like beat of an iamb the anapest extends the duration between stresses, which in turn amplifies the emphasis on those stressed syllables.

-

One of the benefits to using an anapest is it has a sing-songy rhythm.

-

One of the detriments is the sing-songy rhythm.

To overcome the tediousness of this jog-trot rhythm is this writer has swapped out the anapest with the dactyl. And it works!

Did you notice how the author did this in line 3 of the first stanza. and

Did you see it again in line 4 of the second stanza.

This nice metrical switch is fresh and can keep a reader engaged. The metrical variation of 4 beats per line, then 3 beats per line is another surprise. We are not bored or bogged down. In fact, did you not feel like roaring with the last line in the second stanza?

The anapest meter has great variety. It can be cheerful and light but also intense and suspenseful.

EXAMPLE: ANTANACLASIS

All we need --/

Is what’s found in the breeze, --/--/

In the stillness of nothing, --/--/-

In the rustle of trees, --/--/

When we take a deep breath, --/--/

What’s not seen – but is there. . . --/--/

All we need. . . is air. --/--/

ALL WE NEED

By Kathy Wolff

Illustrated by Margaux Meganck

I have scanned this as anapestic/dimeter mostly done in tercets. I saw this poem as an opportunity to show how the author has used the poetic technique of antanaclasis.

What is antanaclasis? In short it is a form of repetition.

Antanaclasis appears with the repetition of a word or phrase, when that word or phrase means something different each time it appears. For example:

-

Did you notice the topical sentence?

-

Did you notice how the answer is given in the two stanzas below it?

Why use antanaclasis?

-

For emphasis: The repetition of a word or phrase serves to highlight its importance.

-

For persuasion: Scientific studies have shown that simply repeating something is one of the most effective ways to convince people of its truth. One most known example is the I HAVE A DREAM speech written by Martin Luther King Jr.

-

For contrast: Sometimes by repeating the same thing in slightly different contexts it is possible to illuminate contrasts. In this way the poem has added layers and emotional depth.

EXAMPLE: CAESURA

My mom brought home a gift for me. -/-/-/-/

I bounded down the stairs, -/-/-/

then opened up the box and found -/-/-/-/

new underpants – six pairs. -/-/ /-

“Thanks, Mom, but what about my friends? -/-/-/-/

I bet they’d love some too.” -/-/-/

“Well, dear, I don’t think those will fit.” -/-/-/-/

I knew just what to do. -/-/-/

I MADE THESE ANTS SOME UNDERPANTS

By Derick wilder

Illustrated by K-Fai Steele

Caesura can occur at the middle of line, the beginning, or at the end of a poetic line.

One of the most powerful tools in any reader's arsenal is the pause. Where do pauses occur in a poem?

-

When a poem becomes monotonous

-

When you want to emphasize a thought or feeling.

-

When you want to create a surprise or produce variation.

-

When you want to slow or speed up the rhythm

-

To jar your reader in some way.

How do you create the pause in your poem?

By means of punctuation.

Comma, dashes, ellipsis, semicolon, or a period.

There are many things to recommend about this book besides the skilled use of the caesura. It has the excellent use of diction, the hilarity factor along with picture appeal. I suggest you go out and get this book to find out.

The other day, I wrote this book. -/-/-/-/

You won’t believe how long it took. -/-/-/-/

It rhymed, and I was super proud. -/-/-/-/

It sounded great when read out loud. -/-/-/-/

But then my sister came along, -/-/-/-/

And now the story sounds all wro – -/-/-/-/

BETTER! ?#!?

THE BOOK THAT ALMOST RHYMED

Written by Omar Abed

Illustrated by Hatem Aly

Can you place prose within metered poetry? Can you mix poetry within prose? Yes! But it cannot be arbitrary, there must be a purpose or reason.

But first you need to ask yourself why? What is the purpose of this insertion?

To keep the story from becoming rigid, mechanical or have the reader checking out.

Notice how this was done in the stanzas above.

Everything is going along fine, until the second stanza. In that stanza the word wrong is interrupted, and a different word explodes on the scene. We stand erect and say. . .what. . .

In other words, we pay attention.

Back to the third stanza. We da dum along. We expect to read the last line as worse but instead a surprise again!

But now we know the reason. The younger sister is interrupting. With her insertion of ideas, she steps all over the rhyme. Hence the purpose of introducing this prose is accomplished. It is seasoned well, and we want to keep on reading. We want to know how this story is going to end up.

I say WELL DONE!

Giant sky, brightest blue, /-//-/

like an artist painted you. /-/-/-/

How I wonder, wonder why, /-/-/-/

Why are you so blue, big sky? /-/-/-/

Me? I’m scattered rays of sun – /-/-/-/

Many colors, not just one. /-/-/-/

Blue is what the eye perceives, /-/-/-/

And what you see, the brain believes! -/-/-/-/

WONDER WHY

by Lisa Varchol Perron

illustrated by Nik Henderson

A conversation poem is a dialogue between two or more voices in which the characters are revealed through dialogue. And the entire story is told through dialogue.

-

Were you able to know who is speaking in this story?

-

Because there are no dialogue tags, ask yourself, how did you know?

-

Could it have been because of the slight difference in style and diction?

This is a yummy sort of book. Full of information but presented through a poetic form. We read terms such as wavelength and Coriolis effect and atmospheric shock waves. We must never underestimate a child’s ability to absorb and learn.

The sun has set and gone to sleep, -/-/-/-/

The moon is shining high. -/-/-/

The wind is gently whispering, -/-/-/-/

Stars twinkle in the sky. //-/-/

Everywhere across the land, /-/-/-/

Across the waters, too. . . -/-/-/

Some very sleepy creatures //-/-/-

Are waiting just for you. -/-/-/

MOONLIGHT, GOODNIGHT

Written by Elisabeth Sophia

Illustrated by Karina Jambrak

A spondee is where two words carry equal weight in a sentence. Like DUM DUM. Or this DUM DUM can be two syllable words. Like its title Moonlight, Goodnight. Both syllables carry their own weight.

When combined with other metrical patterns it often changes the pace of a poem. To learn how to scan a poem with spondees try reading it out loud.

Have you found the spondees in the stanzas above? It still reads like silk.

What purpose does a spondee serve?

-

To emphasize certain words.

-

To change the pace.

-

To avoid a monotone-like form of reading.

This picture story book is lush and lovely.

Once I reach the beach I stop /-/-/-/

and stare across the sea -/-/-/

with all the fun of summertime -/-/-/-/

stretched out in front of me. -/-/-/

I spend day one among the crowds -/-/-/-/

who paddle, swim and play -/-/-/

until the tide eats up the sand -/-/-/-/

and ushers us away. -/-/-/

MOUSE BY THE SEA

Written by William Snow

Illustrated by Alice Melvin

An iamb is an unaccented syllable, followed by a long and accented syllable. Similar to da DUM.

The function of iambic meter is to create a speech that should have a regular pattern. It makes a normal speech fit into heightened formality and dramatic form. It gives it a rhythmic sense; and creates an emotional experience.

You begin to feel the elegance and power of words.

-

Did you notice how this was written in a natural spoken form?

-

Did you notice no inversion of words?

This is a gorgeous book. I think it will be read over and over.

WHERE THE DEER SLIP THROUGH

Written by Katey Howes

Illustrated by Beth Krommes

This is the hedge that grew and grew.

The wall of stone a bit askew.

They guard the yard. The barn does, too.

While just outside, hills roll and rise away off into the pines.

This is the gap where the deer slip through,

when the sky is still more pink than blue.

Nibble and nudge and startle and dash away off into the

pines.

I return to one of my favorite poetry forms. Cumulative poetry or tales. But what is a cumulative story?

Cumulative stories refer to a structure in which details and dialogue repeat and build upon each other during the story. Cumulative stories create a pattern, and the plot lines become predictable.

These stories can be playful, nonsensical. They may rhyme or not rhyme.

Cumulative tales are good for improving speech, language development, and literacy fluency. Because children encounter the same vocabulary multiple times, words are reinforced.

-

Children can practice pronunciation and sentence construction.

-

Children predict what comes next, which strengthens memory and comprehension.

This story was an inspiration to me. It caused me to go back to one manuscript and rewrite it as a cumulative tale.

Do you have a manuscript that needs something but you’re not sure what? How about rewriting it?

When it comes to anything that we do, practice helps us improve. View this as another practice session. See what happens.

THE MONARCH

Written by Kirsten Hall and Isabelle Arsenault

In the garden through the trees, /-/-/-/

buzzing by are honeybees! /-/-/-/

But then – Ooh! Look up! -/-/-/

What’s that? In the air! /-/-/

Over here? Over there? /-//-/

It’s the start of a band-new story. . . -/-/-/-/-

It begins on this leaf – /-/-/-

In a moment so brief – /-/-/-

I’ve had many an editor inform me that my poems were cluttered with commas. When I look back, I reluctantly agree.

There are those who ask, “do poems even need punctuation?” Most do not. A simple line break will give you the pause you want.

But you can make punctuation work for you instead of against you. Here are some suggestions.

-

Capitalization: This will create a degree of emphasis.

-

Periods: A period is different from exclamation marks in that it is somewhat dull.

-

Exclamation mark: This is to generate excitement!

-

Commas: These are used to emphasis a slight pause, a separate list. They are weak punctuation marks, but they do create a tone.

-

Semicolons: These create an extended pause. They link two ideas and allow the reader to see how these ideas are related.

-

Dashes: These are dramatic pauses. They force the reader to pay attention.

Did you notice the punctuations mentioned above are all about the “pause”? It is about the artistry of slowing down, emotional rhythm, cadence and bringing words to life.

Now let’s go back to the poem in this delightful book. First read it out loud to yourself. Did you find yourself stopping and starting and pausing, yet briefly?

There is a lot of punctuation used. But it mimics the movement of a butterfly as it skitters and flutters about. Landing here and there but never staying too long. This is the mood created.

One more thought. Is there enough room in the market for yet another monarch book? YES! This book is as elegant as the monarch itself. Gorgeous!

THE COUCH IN THE YARD

Written by Kate Hoefler

Illustrated by Dena Seiferling

This is the house. /--/

This is the house in the hills up high, /--/--/-/

with a rusted old car in the sweet joe – pye – --/--/--/-/

where the clothesline sways on a dogwood breeze, --/-/--/-/

where the road goes to ruts and fades into trees. --/--/-/--/

This is the porch that is crooked and marred. /--/--/--/

This is the couch that sits in the yard. /--/-/--/

These are the folks with tools and a heart /--/-/--/

who work on the car to get it to start – -/--/-/--/

There is much to comment on with this picture book, but I will choose something I’ve not used for a while. Imagery.

Imagery is used to convey feelings that are difficult to describe. Have you ever felt that mere words would cheapen or diminish the emotion you are experiencing? This is where imagery comes in.

A writer paints a picture for you. They create an image.

Creating an image involves using all your senses.

A poet will not just describe a feeling but rather invoke a feeling with the image.

Also important are descriptors, phrases added to give more information. This is where you get specific.

-

Did you see the image painted by the rusty old car?

-

Did you see the clothesline swaying on a dogwood breeze?

-

Did you feel the road that goes to ruts and fades into trees?

So what do you need to do? Go through each word in your manuscript to see if it fits into the image you are trying to create or the mood you want.

I had lots of feels with this book. It will be a favorite.

I DON’T WANT TO HIBERNATE!

Written by Anna Ouchchy

Illustrated by Raahat Kauji

Sudden snowfall, icy air /-/-/-/

Cozy burrow dig with care. /-/-/-/

Three prepare for winter rest – /-/-/-/

Mommy, daddy, little Tess. /-/-/-/

Yawning parents tuck her in, /-/-/-/

Pull up blankets to her chin. /-/-/-/

“Close your eyes, it’s cold. It’s late.” /-/-/-/

“I DON’T WANNA HIBERNATE!” /-/-/-/

“Bedtime books will do the trick. /-/-/-/

Look – your favorites take your pick.” /-/-/-/

Daddy reads until – snore. . .snore. . . snore. . . /-/-/ / / /

Tiptoes out and shuts the door. /-/-/-/

A trochee is a two-syllable metrical pattern in poetry in which a stressed syllable is followed by an unstressed syllable.

Trochaic meter is a falling meter because it lands on an unstressed beat.

The base meter has four beats across each line and each stanza having four lines, with a consistent rhyming couplet of ABAB.

Perhaps you have also noticed the metrical variation. This author has played around with the hard beats.

-

The spondees in the third stanza of snore. . .snore. . .snore. . .? We see the replacement of the soft beats with an ellipsis. This forces you to speak in a low tone, thereby mixing things up. But then -

-

Did you notice the excitement of the last line in the second stanza? I DON’T WANT TO HIBERNATE! Does this not make you sit up and pay attention?

Varied meters are a good thing.

And this book is lots of FUN!

Written by Kaye Umansky

Illustrated by Alice McKinley

This is MY rock! Huh?!

Zzzzz. . .

This rock is mine! -/-/

ZZZZ. . .

I’m always here come rain or shine. -/-/-/-/

I saw it first. It suits me fine. -/-/-/-/

This rock is mine! -/-/

This is MY rock. It’s mine alone. /-/ /-/-/

You want a rock? Go find your own. -/-/-/-/

I do not like your bossy tone. -/-/-/-/

This rock is MINE! -/-/

This is MY rock! My stuff is here. /-/ /-/-/

My sandwiches, my fishing gear. -/---/-/

I think I’ve made it very clear. -/-/-/-/

This rock is MINE! -/-/

A conversation poem is a dialogue between two or more voices of dialogue. Dialogue is power! This is a story of how to work together.

The use of formatting to show the alternating speakers is important.

-

Did you notice there is no narrative exposition?

-

Did you notice that the entire story is told through dialogue?

-

Did you notice the mood and character revealed through their conversations?

Written by Lynn Becker

Art by Scott Brundage

What do you do with a grumpy kraken? /-/-/-/-/-

Crabby, cranky, crusty kraken? /-/-/-/-

What do you do with a grumpy kraken? /-/-/-/-/-

Kraken in the briny. /-/-/-

Share some joe's and your best riddle, /-/-/-/-

Feed her cakes from the Cookie griddle, /-/--/-/-

Teach her how to bow the fiddle, /-/-/-/-

Kraken in the briny. /-/-/-

Yo! Ho! And Arrr! We’re flooding, / /-/-/-

Yo! Ho! The deck is mudding, / /-/-/-

Yo! Ho! our anchor’s thudding, / /-/-/-

Kraken in the briny. /-/-/-

Refrain is a verse, a line, a set, or a group of lines that appears at the end of stanza, or appears where a poem divides into different sections. It originated in France, where it is popular as, refraindre, which means “to repeat.”

A refrain can include rhymes, but it is not necessarily.

Ever heard a song on the radio and been unable to get it out of your head? It likely got stuck there because of the chorus. In poetry, the chorus is called a refrain. It helps a lot that this story is set to actual music.

When a story becomes music, the child will often ask for that story to be read again and again. If the story is informational, then that information is reinforced.

By Lisa Wheeler

Illustrations by Barry Gott

Each year on April twenty-two -/-/-/-/

The dinos know just what to do. -/-/-/-/

The world needs help to keep it clean. -/-/-/-/

It’s Dino-Earth Day . . . Let’s go green! -/-/- / / /

How do dinos show they care? /-/-/-/

Driving less make cleaner air! /-/-/-/

Raptor walks to work each Day. /-/-/-/

Sego scooters. “Clear the way!” /-/-/-/

Gallimimus rides her bike. /-/-/-/

T. Rex skates. The Diplos hike. /-/-/-/

I must first point out the iambic meter used in this delightful book.

An iamb is a two-syllable metrical pattern where one unstressed syllable is followed by a stressed syllable. The word "define" is an iamb. It has an unstressed syllable followed by the stressed syllable, as in deDUM. Because the iambic is like a heartbeat it is quite easy to become lulled to sleep. To overcome this poets will often swap out the iamb with the trochee. This still works because what matters (what we count) is the hard beats.

Now we can get to the part I love most about this book!

Informational fiction!

-

Did you notice how each type of dinosaur is introduced, what they are called and what they look like? Woohoo!

-

Did you see complex words in context? This helps broaden vocabulary. Children’s minds absorb so easily. Woohoo!

When a story becomes music, the child will often ask for that story to be read again and again and again. If the story is informational, then the information is reinforced again and again and again.

PIE-RATS

Written by Lisa Frenkel Riddiough

Illustrated by David Mottram

Pie-rats sail the starry night, /-/-/-/

Seeking treasures baked just right. /-/-/-/

Pie-rats don’t want gold doubloons – /-/-/-/

Their bounty comes on forks and spoons. -/-/-/-/

Out at sea, their stomachs hurt, /-/-/-/

Pie-rats’ mission : find dessert. /-/-/-/

From the poop deck, hears them cry: /-/-/-/

PIE, PIE, PIE, PIE! / / / /

A spondee is a foot of two syllables, both of which are long in equally stressed meter. Spondee has a DUM-DUM stress pattern.

The purpose of using a spondee is to heighten words, or feelings or to make a story take on drama.

A spondee can give the poem energy. It can come across as a command. Spondees are usually short, staccato and forceful.

-

With the last line did you not feel the emotional tension created by that repetition?

-

With the last line did you not feel like you must pay attention, even rise to action?

Princess Prudence loved that frog, /-/-/-/

her bunny and her spotted dog, -/-/-/-/

but nothing else could quite compare -/-/-/-/

to little Ted, her royal bear. -/-/-/-/

She took him here; she took him there – -/-/-/-/

she took that teddy everywhere. . . -/-/-/-/

The supermarket and the zoo. . . -/-/-/-/

She took him to the bathroom, too! -/-/-/-/

But once upon a sunny day, -/-/-/-/

NEVER MESS WITH A PIRATE PRINCESS!

By Holly Ryan

Art by Sian Roberts

What is a couplet? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A couplet is two lines of poetry that form a rhyme or are separated from other lines by a double line break.

-

Couplets do not have to be stand-alone stanzas. Instead, a couplet may be differentiated because it forms a complete sentence, or to specify which two lines.

-

Couplets do not have to rhyme, though they often do.

-

A couplet may be open or closed, meaning that each line may make up a complete sentence, or the sentence may carry from one line into the next.

-

It's easy to identify a couplet when the couplet is a stanza of only two lines, but the term "couplet" may also be used to specify a pair of consecutive lines within a longer stanza.

Couplets are included in poems because of their constant rhythm and the pairing can draw attention to a specific thought.

-

Did you notice how the thought in one stanza bleeding into the next stanza?

-

Did this make you pick up your pace of reading?

This book was a super fun read!

EXAMPLE: METRICAL VARIATION

If you go into the woods, /-/-/-/

as every growing child should, -/-/-/ /

among the wonder all around, -/-/-/-/

you’ll find a trail if you look down. -/-/-/-/

Follow footprints on the floor /-/-/-/

of those who came here long before. -/-/-/-/

Leaving all you know behind, /-/-/-/

there’s a secret place you’ll find, /-/-/-/

Hidden high above the ground. . . /-/-/-/

TREEHOUSE TOWN

Written by Gideon Sterer

Illustrated by Charlie Mylie

Perfect meter can become humdrum. The language fails to engage the reader; it has no emotional impact. There are ways to fix this. Enter. . .

Metrical variation to the rescue!

I mention just three examples because they appear in these couplets above. You will HAVE to read the rest for yourself.

Spondee is a beat in a poetic line that consists of two accented syllables (stressed/stressed) or DUM-DUM. The purpose of using spondaic meter is to emphasize particular words, and to create heightened feeling, or provide an emotional experience.

-

Did you notice the spondee in the second line?

Truncated is a line of poetry that is missing one or more syllables from the middle or the end of a line.

-

Did you notice that I have scanned these couplets as trochaic meter. DUM da!

But where is the soft beat at the end of these lines? Each and every one of them has been truncated! Oh no! In scanning poetry, we must count the hard beats. The soft beats, they are important, just not so important. Why? Because when we read, we naturally fill in the soft beats with a pause.

Could you say that this is an iambic meter with a few lines that are headless? Yes! Oh no! Are we beheading this time? Yes again.

-

Hypercatalectic: The term for a metrical foot to which one or more unstressed syllables have been added.

-

Catalectic: This is a term for a soft metrical beat that has been subtracted.

So, in conclusion, mix up your meter because you want to avoid tedium, change the pace, enhance a phrase word or action. I know this post is like the previous one. But I just had to add this book!

The pictures in this book are extraordinary. Children will discover something new each time they look.

EXAMPLE: HYPERCATALECTIC, CATALECTIC, PYRRHUS

Glowing coals are finally ready. /-/-/-/-

Roscoe holds his sharp stick steady. /-/-/-/-

Slowly turned and gently roasted, /-/-/-/-

Soon that fluffy puff is toasted. /-/-/-/-

Crispy grahams wait on a plate. /-/-/--/

(Roscoe stacked them, nice and straight.) /-/-/-/

He adds a creamy chocolate square. . . -/-/-/-/

“Is that for me?” asks Grizzly Bear. -/-/-/-/

Roscoe shrugs, “Bon appe’tit!” /-/-/-/

Grizzly gulps the gooey treat. /-/-/-/

MAKE MORE S’MORES

Written by Cathy Ballou Mealy

Illustrated by Ariel Landy

Poetry is about language. Poetry evokes awareness and an emotional response. It is arranged by meaning, sound, and rhythm.

There are techniques that are allowed in the choices we make with our poetry. I will focus on hypercatalectic, catalectic and Pyrrhus.

-

Catalectic – A missing soft beat at the beginning or end of a line.

-

Hypercatalectic – An added soft beat at the beginning or end of a line.

-

Pyrrhus – An added soft beat in the middle of a line.

Why would we want to use any of these techniques?

To take away the monotony, to make you sit up and pay attention, and laugh.

Let’s see how this author skillfully used these in her style of writing.

-

Did you notice the added soft beat in line 5?

-

Did you notice the added soft beat at the beginning of lines 7 & 8?

The important point for all of us is that these are soft beats. We can play with them a little.

And how about reading a funny poem to make your day!

EXAMPLE: THE ANAPEST

It starts when a rhythm drips onto your skin. -/--/--/--/

A drizzle or downpour that seeps its way in. -/--/--/--/

Oh, DUM da da, DUM da da! Drenched in the beat, -/--/--/--/

you splash in the rhythm from forehead to feet. -/--/--/--/

It soaks through your skin to the layers below, -/--/--/--/

each blood cell and platelet swept up in the flow. -/--/--/--/

Your body's been thirsty but did not know why. -/--/--/--/

(Life without poetry often feels dry.) -/-/--/--/

A POEM GROWS INSIDE YOU

Written by Katey Howes

Illustrated by Heather Brockman Lee

In my previous post I wrote about the dactyl meter. In this post I will show the opposite of dactyl, the anapest meter. Could you say that this is really a footless dactyl with an added soft beat at the beginning? Yes. I saw it as anapest with a soft beat missing from the beginning. What is important is that the hard beats remain the same.

In poetry, an anapest is a metrical foot with two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable.

The word “anapest” comes from the Latin anapaestus, which is derived from the Greek anápaistos, or “struck back”—a reference to how the anapest is a reversed dactyl.

Anapestic meter has a rolling feel to it, like the sound of horses trotting. Because it sounds song-like, anapest is popular in rhymes for children.

-

Did you notice how these two opening stanzas introduce a lighthearted romping tone?

-

Did your tongue feel like it is waltzing across the page?

This rhythm and rhyme combo makes for some catchy lines that stick in your mind long after you've finished reading the poem.

I highly recommend it!

EXAMPLE: THE DACTYL

Aa

Ape picks an apple for Aardvark below. /--/--/--/

Bb

Bat put a bandage on Brown Bear’s big toe. /--/--/--/

Cc

Cow covers Cat with a coat cause he’s cold. /--/--/--/

Dd

Donkey gives Dog her dolly to hold. /--/-/--/

K IS FOR KINDNESS

By Rina Horiuchi

Art by Risa Horiuchi

With this picture book I could have used alliteration as an example. Or an acrostic poem as an example. Instead I decided to focus on the dactyl. Just because it is unusual to find in poetry. Here is what the use of the dactyl is about.

Dactyl is a metrical foot containing three syllables in which the first one is accented, followed by second and third unaccented syllables.

Could you have scanned this as anapest that is headless? Yes. Could you have scanned this as dactyl that is footless? Yes. That is because Dactyl is opposite to anapestic meter.

Dactyl meter gives the lines a romping movement.

The dactyl’s basic nature is that poets can use it to place the emphasis exactly where they want it to go. Thereby emphasizing something important.

-

Did you notice how the child will be able to identify the alphabet in each sentence and how it is pronounced?

-

Did you notice how fun this was to read?

EXAMPLE: METRICAL VARIATION

Shhh. . .

Tiptoe by. Don’t make a peep. /-/-/-/

It’s daytime, so the skunk’s asleep. -/-/-/-/

If he’s disturbed, he might just spray. -/-/-/-/

Let him snooze. . . now sneak away. /-/-/-/

You inched ahead and took a peek. -/-/-/-/

But if he sprays you. . .you will reek. -/-/-/-/

For weeks, you’ll stink from head to toe. -/-/-/-/

If you’re smart, you’ll turn and go. /-/-/-/

IF YOU WAKE A SKUNK

Written by Carol Doeringer

Illustrated by Florence Weiser

Metrical variation is a technique poets use to -

-

To spice up their poem.

-

To avoid a tedious sing-songy meter.

-

To emphasize mood.

How does one go about using metrical variation?

-

Hypercatalectic: Where one or more unstressed syllables have been added.

-

Catalectic: Where one or two unstressed syllables have been subtracted.

-

Important to note! We are referring to UNSTRESSED syllables.

How has this author accomplished this?

-

Did you notice that there has been added a soft beat at the beginning lines 2, 3, 5 and 6.

-

Did you notice the ellipses in two of the stanzas? Did this cause you to change your tone? Did you say, run, run, run!

Oh but they did not! Find out what happens next!

EXAMPLE: CEASURA

I had a poem in my pocket, -/-/-/-/-

but my pocket got a rip. /-/-/-/

Rhymes tumbled down my leg, -/-/-/

and trickled from my hip. -/-/-/

Slipping, sliding, dipping, diving, /-/-/-/-

rhythms hit the ground. Then... /-/-/ /

A whirling, twirling, swirling wind -/-/-/-/

Blew all my rhymes around. -/-/-/

A POEM IN MY POCKET

By Chris Tougas

Art by Jose’e Bisaillon

Everyone speaks, and everyone breathes while speaking. Poetry also uses pauses in its lines.

One such pause is known as “caesura,” which is a rhythmical pause in a poetic line. Though it can occur in the middle of a line, or sometimes at the beginning and the end. At times, it occurs with punctuation; at other times it does not.

-

Did you notice the caesura in the second line of the second stanza?

-

Did you notice how this caused you to pause?

-

Did you notice the expectation this created?

Caesura is a poetic technique to create drama, enhance momentum and complexity.

EXAMPLE: THE ANADIPLOSIS

Do your ears hang low? /-/-/

Do they wobble to and fro? /-/-/-/

Can you tie them in a knot? /-/-/-/

Can you tie them in a bow? /-/-/-/

Can you throw them o’er your shoulder /-/-/-/-

Like a continental soldier? /-/-/-/-

Do your ears hang low? /-/-/

DO YOUR EARS HANG LOW

written by Jenny Cooper

Illustrated by Jenny Cooper

Anadiplosis occurs when a word or group of words located at the end of one clause or sentence is repeated at or near the beginning of the following clause or sentence.

This piques the interest of the reader immediately with the story. In the case of this poem, we see that we are about to embark on a comical journey.

Overall, as a literary device, anadiplosis functions as a means of emphasizing words and ideas. Readers often remember passages that feature this type of repetition. This not only enhances a reader’s experience and enjoyment of language because it resembles music.

The anadiplosis is not limited to poetry but works well with prose and in speeches. In speeches it is done as a call to action and creates a powerful urgency in making a choice.

Can you pick out the anadiplosis repetition the stanzas?

EXAMPLE: THE APOSTROPHE VOICE

OH Bad Morning,

Eyes are crusty, bones are rusty. /-/-/-/-

Why do all my teeth feel dusty? /-/-/-/-

All I see is gray ahead. /-/-/-/

Can’t I stay inside my bed? /-/-/-/

Oh you Bad Morning.

Oh Too Much Milk in My Cereal,

Soggy, squishy? Boggy, mush! /-/-/-/

You turned my crispy into gushy! -/-/-/-/-

My flakes are drenched. My fists are clenched. -/-/-/-/

Oh you Too Much MilK!

ODE TO A BAD DAY

Written by Chelsea Lin Wallace

Illustrated by Hyewon Yum

Words have the power to transport us to different worlds, evoke our deepest emotions, and connect us to each other. Poetry is a language that is designed to move us.

In the apostrophe voice, the writer speaks to a person, animal, or something abstract.

-

Did you notice how the main character was addressing the BAD Day?

-

Did you notice how the author allowed the character to in effect offer a soliloquy?

-

Did you notice how this poem allowed the main character to illuminate an emotional state.

-

Did you notice how this poem allowed the main character to express a thought process?

-

Did you notice the child-like authentic voice?

This poem is a masterpiece in celebrating the frustration, the boredom and the upsets of a bad day.

EXAMPLE: THE ENJAMBMENT

Imagine moms beneath the waves -/-/-/-/

with lots of love to share. -/-/-/

Whatever might they say or do -/-/-/-/

to show how much they care? -/-/-/

Hermit crab shops here and there /-/-/-/

to find a roomy shell. -/-/-/

She gently backs her baby in. -/-/-/-/

“Now, doesn’t that fit well?” -/-/-/

OCEANS OF LOVE

By Janet Lawler

Illustrated by Holly Clifton-Brown

The term enjambment comes from the French words jambe, meaning leg, and enjamber, meaning to straddle or step over. This is a literary device that allows the poet to compose a sentence that runs on to the next line before reaching a full stop.

Without any type of punctuation enjambment creates suspense and momentum.

-

Did you notice that the reader feels propelled forward through the poem?

-

Did you notice how these interruptions arouse uncertainty, an uneasy pause, encouraging readers to move to the next line.

LET’S BUILD A LITTLE TRAIN

By Julia Richardson

Illustrated by Ryan O’Rourke

EXAMPLE: ONOMATOPOEIA

Let’s build a little train -/-/-/

To chug along the track -/-/-/

That goes from here to there -/-/-/

And circles round and back. -/-/-/

CHOOOOOOO!

We’ll need a giant warehouse -/-/-/-

With lots of helping hands, -/-/-/

And engineer will manage -/-/-/-

And supervise commands. -/-/-/

Onomatopoeia indicates a word that sounds like what it refers to.

So why use onomatopoeia in your writing?

For example. You could say your house blew up. Or you could say my house went BOOM!

You could say you dropped the water balloon on the floor. Or you could say the water balloon went SPLAT.

In each of the second examples, the reader supplies the sensory effects with their own imagination. The imaginary world becomes their own.

-

Did you notice how the words “Chooooo!” and “Chugga!” heightened the experience for the reader?

-

Can you not hear your own child repeating these words? Perhaps over and over?

-

Did you notice how it broke up the monotony of the iamb with fun, lively and playful words?

Do you have a good WIP? Want to make it better than good? Why not insert some onomatopoeia. See what happens when you do.

THE CRAB BALLET

By Ren’ee LaTulippe

Art by Ce’cile Metzger

EXAMPLE: POETRY AND A FOREIGN LANGUAGE

turtles spiral in between. /-/-/-/

A sea horse pair glides on the scene, -/-/-/-/

Bows deep and low, the soubresaut! -/-/-/-/

An elegant marine routine. -/-/-/-/

This is a story of how the tide is like ballet, with each character appearing then disappearing. We feel like we are watching theater with a theme, story and atmosphere.

But first a little introduction. Allow me to digress.

Ballet is made up of gestures, movements and ebb and flow, in many ways is like a tide.

The French phrasing has remained universal in Ballet. Ballet dancers across the world learn and can communicate with this universal ballet terminology.

How about using foreign words to infuse your poem with something rich and a taste of the unexplored?

Take your meter and rhythm away from the predictable.

You will of course need access to a good foreign language dictionary.

You will also need back matter to explain to the reader how to pronounce the words and their meaning.

EXAMPLE: THE LIST POEM

Kindness is sometimes /--/-

a cup and a card -/--/

or a ladder, a truck, and a tree; --/--/--/

a scratch and a cuddle, -/--/-

a rake and a yard, -/--/

a cookie, a carrot, a key. -/--/--/

it’s seeds and a feeder, -/--/-

A seat on the train, -/--/

A daisy, a peach, or a pie; -/--/--/

A wave at a baker, -/--/-

a boost on a crane, -/--/

a sandwich shared up in the sky. -/--/--/

FINDING KINDNESS

By Deborah Underwood

Illustrated by Irene Chan

List poems are perfect when trying to use rhyme in picture books.

You are not forced into a dramatic arc.

-

Did you notice that list poem?

-

Did you notice the lyrical, rhythmical tone? If you were to read the rest of this book you would notice it’s not heavy in end rhymes. The rhyme is interspersed, like a flavorful spice.

EXAMPLE: INTERNAL RHYME

“Hurry-scurry, kids,” called Mom.

“Let’s jiggety-jog into town in our gracious-spacious automobile.”

Max and Molly hurry-scurried into the car.

“Okey-dokey?” asked Mom.

“I’m squished,” said Max.

“Move over, Molly.”

“I’m squashed,” said Molly.

“Mover over, Max.”

SQUISH SQUASH SQUISHED

by Rebecca Kraft Rector

Art by Dana Wulfekotte

Internal rhyme occurs in the middle, or anywhere, in lines of poetry, except the end. It is a lyrical device.

You can take a story that has saturated the market and set it up a notch.

-

Did you notice the musicality in this story?

-

Did you notice the fun and hilarity factor?

So just go ahead and tell you story. Don’t be forced or constrained into a metrical pattern where the story is serving the rhyme.

EXAMPLE: THE IAMB

Once upon a forest floor /-/-/-/

A snout poked out a burrowed door -/-/-/-/

And wheezed and sneezed for on the breeze -/-/-/-/

There came a hint of . . . POO. -/-/-/

Sniff, sniff? Went mouse. Whiff, whiff! Went Mouse. -/-/-/-/

“Who left this poo outside my house?” -/-/-/-/

“I must undo this mystery. -/-/-/-/

Poo-dunit?” Oh, Squiiiiirel. . . /-/-/-

“Not me!” said Squirrel, who smelled it all. -/-/-/-/-

“This poo is big! My poo is small. -/-/-/-/

Ask Skunk. Oh, Skuuunk. . . -///-

POO-DUNIT

A forest Floor Mystery

By Katelyn Aronson

Illustrated by Stephanie Laberis

The iamb is a (da- DUM) rhythm. Because of its even pacing it is often referred to as the heartbeat rhythm.

This is all very lovely but why exactly should we study rhythm? In poetry it’s all about the -

-

Emotional response.

-

Elevating a piece of work.

-

The pleasure of listening.

-

Creating images.

-

Creating a mood.

-

Painting with words.

Just like a heartbeat, iambs can lull you to sleep. Oh, what to do! Wait a minute!

Did you notice how this author chose to rouse us out of our boredom?

-

With a few spondees thrown in there.

-

Inserting metrical variation.

-

With a line of dialogue.

-

Adding lines that rhyme with nothing! Yes, you can do that!

-

How did you react when you read that fourth line?

Did you sit up like I did?

This is a delightful informational fiction book. So childlike and fun!

SUPER SECRET AGENT GUY

Written by Kira Bigwood

Illustrated by Celia Krampien

EXAMPLE: THE TROCHEE

Secret, secret agent guy, /-/-/-/

Working for the FBI. /-/-/ / /

On a mission from the top: /-/-/-/

Get your gear on – first things first – /-/-/-/

Pausing just to quench your thirst. /-/-/-/

Grappling hook and nighttime specs, /-/-/-/

Walkie – talkies, check check check! /-/-/ / /

The trochee is the opposite if the iamb. It begins with a hard beat followed by a soft beat.

The word trochee is Greek and comes from the word “wheel” which is often associate with a rolling effect and momentum.

Imagine the soft padding of your feet in the sand as you jog. We start with the propulsion. Then the body is momentarily suspended. Ending with the interruption of a fall. The trochee has a similar cascading effect as each foot is running into the beginning of the next foot. The result is that the trochaic meter has a strong forward momentum.

The trochee gives the reader a pause, a surprise, and an opportunity to enjoy a different type of poetry.

This is a delightful picture book and what fun to read! Wait for the twist at the end!

EXAMPLE: BLANK VERSE

A child is born one winter day. -/-/-/-/

His mother calls him Lamb. -/-/-/

She hums a tune that has no words -/-/-/-/

And holds her baby’s hand. -/-/-/

The baby wakes. The baby sleeps. -/-/-/-/

And grow. One day he stands. -/-/-/

He falters like a wobbly colt. -/-/-/-/

His mother holds his hands. -/-/-/

The baby sleeps. The baby wakes. -/-/-/-/

He claps, again, again, -/-/-/

For hot cross buns. He pat-a-cakes -/-/-/-/

Just like a baker’s man. -/-/-/

LOVING HANDS

By Tony Hohnson

Art by Amy June Bates

Blank verse is metered poetry but does not have to rhyme.

Blank verse will often use slant rhyme or near rhyme. Though even this is not required.

How did this poet make use of the blank verse?

-

This metered poem is done in quatrains with an alternation of tri meter/tetrameter.

-

The author has made ample use of the slant rhyme.

-

Example: Lamb/hands, again/man. You will see many more examples throughout the rest of this poem.

Blank verse allows you to tell you story with greater flexibility, without the challenges of the rules of rhyme.

EXAMPLE: THE SPONDEE

Bored, Ignored, or feeling down? /-/-/-/

Need some fancy in your town? /-/-/-/

Want some shine upon your crown? /-/-/-/

Just add glitter!

Try a speck, a fleck a sprinkle, /-/-/-/-

see how things begin to twinkle. /-/-/-/-

A little here, a little there. -/-/-/-/

Glitter glitter everywhere!

Is your bedroom such a bore? /-/-/-/

How bout sparkle on your door? /-/-/-/

Could your art use something more? /-/-/-/

Just add glitter!

just add

GLITTER

by Angela Diterlizzi

art by Smantha Cotterill

Spondee is a metrical device where you put an equal amount of stress on each word. It is commonly used to change the pace of a poem. To add a heightened feeling or emotional experience. It adds expectancy and or excitement.

-

Did you notice the use of the Spondee in the last line?

-

Did you notice that the last line in the stanza rhymes with nothing?

-

Did you feel yourself adding additional emphasis to this phrase?

Children will catch on fast, and love repeating the line with you.

EXAMPLE: CUMULATIVE STORY STRUCTURE

This is the mess that we made.

These are the fish that swim in the mess that we made.

This is the seal that eats the fish that swim in the mess that we made.

This is the net that catches the seal, that eats the fish that swim in the mess that we made.

This is the boat of welded steel, that dumps the net, that catches the seal, that eats the fish that swim in the mess that we made.

THE MESS THAT WE MADE

By Michelle Lord

Art by Julia Blattman

A Cumulative Story is a story that builds on a pattern. It starts with one person, place, thing, or event. Each time a new person, place, thing, or event is shown, all the previous ones are repeated.

-

Each event reinforces the initiating problem of the story and a new attempt at solving it. It helps children to think of different solutions.

-

Did you notice the problem, initiating event, character intentions and desires, and moral are there?

-

This is fun because children soon pick up on the refrain and increase their own vocabulary.

-

Did you notice how each event add momentum? Thereby increasing tension.

EXAMPLE: STRESSED BEATS

White cat Black cat /-/-

Blue cat Brown cat /-/-

High cat Low cat /-/-

Always upside-down cat. /-/-/-

Fluffed cat Bare cat /-/-

Round cat Square cat /-/-

Long cat short cat /-/-

Rarely-ever-there cat. /-/-/-

Bold cat shy cat /-/-

Nice cat mean cat /-/-

Wet cat mud cat /-/-

Super-duper clean cat. /-/-/-

HAPPY CATS

By Catherine Amari and Anouk Han

Art by Erni Lenox

This is a poem picture book. This has a specific meter and rhyme scheme. The first three lines are trochee/ dimeter. The last line is trochee/ trimeter.

You might thing this is a simple rhyming book. Until you look further.

Did you notice that there are no end rhymes. Each line ends with cat, cat, cat. That is because the second to last word is the one that rhymes. We do not have to rhyme the last word. The only hard and fast rule is for a rhyme to land on a stressed beat.

Why not give it a go yourself? Write a poem using this technique of rhyming a stressed beat anywhere in the line. See it does not surprise you and refresh you.

Pick a stanza pattern you want. Make sure it is consistent. And have fun!

EXAMPLE: THE SIMILIE

I love you like yellow. -/--/-

I love you like green. -/--/

Like flowe ry orchid -/--/-

And sweet tange rine. -/ /-/

I love you like silly, -/--/-

I love you like mud. -/--/

Like joyous and jolly. -/--/-

Like silent and sad. -/--/

Like crunchy and crispy. -/--/-

Like sweet and like tart. -/--/

I love you like crazy -/--/-

With all of my heart. -/--/

I LOVE YOU LIKE YELLOW

By Andrea Beaty

Art by Vashti Harrison

A simile is a figure of speech that makes a comparison between two non-similar things using the words like or as. This is useful for using images or concepts to state something abstract.

Have you ever found that words are not enough? Have you ever felt that there are no words to express how you feel? This is where a simile comes in.

-

Did you notice how the feelings of yellow and green are described in the next line?

-

Did you notice how these similes evoke an emotion or memory?

You will have to explore the playful language with the pictures in this delightful book.

EXAMPLE: DICTION

Sun beach. Rise beach. Pail in hand. /-/-/-/

Found a dollar in the sand. /-/-/-/

Cool toes. What next? Who knows? /-/-/ /

Here comes the ocean! /--/-

Soft beach. Warm beach. Dig a seat. /-/-/-/

Something's nibbling on my feet! /-/-/-/

Hide those toes. What next? Who knows? /-/-/-/

Here comes the ocean! /--/-

HERE COMES OCEAN

By Meg Fleming

Art by Paola Zakimi

Diction, or choice of words, often separates good writing from bad writing.

In literature, writers choose words to create a mood, tone, and atmosphere. The sentence structure should be appropriate to the context in which it is used.

-

Did you notice the refrain also mimics the never-ending waves of the ocean?

-

Did you feel as if you are being rocked to sleep.

Watch your little one's eyes droop.

EXAMPLE: LYRICAL PROSE

One night, under the light of the silvery moon,

all of Bear’s friends were deep asleep.

The Bear- wasn't sleepy he wanted to play.

So he wandered off to find some fun in people town.

Tap.

Poke.

Sniff.

Bare nosed around until he found...

It looked friendly.

Bear plopped down on its lap.

Bingity.

Bing.

Boing!

The Thingity-jig was springy thing.

THE THINGITY-JIG

by Kathleen Doherty

illustrated by Kristyna Litton

What makes a story lyrical?

There are many aspects to discuss.

For the sake of brevity, I will focus on two. Onomatopoeia and internal rhyme.

Onomatopoeia creates a sound effect that mimics the effect. It makes the description more expressive and interesting.

For instance, we could say she fell asleep. Or we could simply write: “Zzzzzz.“

This makes the descriptions livelier and more interesting, appealing directly to the senses of the reader.

Onomatopoeia helps the reader enter the world created. Onomatopoeic words have an effect on the readers’ senses, whether that effect is understood or not.

Internal rhyme is rhyme that occurs in the middle of lines of poetry, instead of at the ends of lines. A single line of poetry can contain internal rhyme (with multiple words in the same line rhyming), or the rhyming words can occur across multiple lines.

This gives you freedom to tell your story, without the confines of meter. It makes your manuscript musical. A manuscript that is fun to read will always stand out and rise above.

BOATS WILL FLOAT

By Andria Warmflash Rosennbaum

Illustrated by Brett Curzon

EXAMPLE: TRUNCATED METER

Boats are bobbing in the bay, /-/-/-/

Waiting to be on their way. /-/-/-/

Longing for the reaching tide. /-/-/-/

Needing to explore and glide. /-/-/-/

Early morning, rise and shine, /-/-/-/

Fishing boats with nets and line. /-/-/-/

Underneath a cloudless sky, /-/-/-/

Dragon boats go flying by. /-/-/-/

When it comes to poetry meter/rhythm/ is more important than rhyme.

But even in this one can fall into a rut and become boring and tedious. One way to overcome this is:

Truncated meter.

This is when one or two soft beats are missing from the end of the line.

-

Did you notice in the lines above that the soft beat is missing at the end of each line? Maybe you didn’t notice. That’s because the soft beats are hardly missed.

The poem is lovely and well done.

In addition, this happens to be an informational picture book. You are being educated in the best way. Facts are woven in without our even noticing. Learning becomes fun.

EXAMPLE: THE ENJAMBMENT

Gisele the giraffe was hungry for leaves, -/--/-/--/

but the juiciest leaves were at the top of the trees. --/--/---/--/

She stretched out her neck, but as hard as she tried, -/--/--/--/

her tongue couldn’t reach, so she plopped down and cried. -/--/--/--/

The zebras and cheetahs and birds gather’d round -/--/--/--/

to find what was making that snuffly sound. -/--/--/--/

And discovered Gisele in a slump by the trees --/--/--/--/

with her neck in a knot and her chin on her knees. --/--/--/--/

HALF A GIRAFFE

By Jodie Parachini

Pictures by Richard Smythe

Enjambment carries an idea or thought over to the next line without a grammatical pause. The absence of punctuation allows for enjambment, and requires the reader to read through a poem’s line break without pausing in order to understand the conclusion of the thought or idea.

Enjambment in poetry creates a rhythm or pace for a poem that is different from end-stopping.

-

Did you notice the enjambments in these to stanzas?

-

When you read did you feel yourself increasing in speed?

EXAMPLE: THE REFRAIN

If I were a tree, -/--/

I know how I’d be. -/--/

I’d stand strong and wide, --/-/

my limbs side to side. --/-/

I’d stand towering, tall, --/--/

high above all, /-/-

my leaves growing big, --/-/

and buds on each twig. -/--/

If I were a tree, -/--/

that’s how I’d be. -/-/

IF I WERE A TREE

By Andrea Zimmerman

Art by Jing J Tsong

Refrain is a poetic device that repeats, at regular intervals, in different stanzas. It also contributes to the rhyme of a poem and emphasizes an idea through repetition.

A refrain can appear anywhere in the poem.

-

Did you notice that the refrain appears before the stanza?

-

Did you notice the refrain appears after the stanza?

This serves an extremely useful purpose with this poem. The ending is poignant, full of heart and takes your breath away.

THE NICE DREAM TRUCK

By Beth Ferry

Illustrated by Brigette Barrager

EXAMPLE: THE ANAPEST

When bedtime is near, --/--/

and teeth are all brushed. -/--/

And the house is asleep, --/--/

and noises are hushed, +-/--/

you might hear a tune, -/--/

You might be in luck. -/--/

You might get a visit. -/--/-

From the NICE DREAM TRUCK. --/ / /

An anapest consists of two unstressed syllables followed by on stressed syllable. This stress pattern gives anapestic verse a light and nimble rhythm that evokes the galloping of a horse or the rolling of ocean waves.

Anapest can become very sing-songy and the reader easily bored and reading tedious. There is a fix to this problem. Enter the truncated/headless meter. What is a truncated meter? What is headless meter?

Headless anapest is a first unstressed syllable that is missing or omitted.

Truncated meter is a line of poetry that is missing a syllable in the middle or at the end of a line.

-

Did you notice the headless meters in lines 1, 2. And lines 5 – 11?

-

Do you have a manuscript in anapest meter? Why not break it up? Insert a headless meter here and there and see what happens!

EXAMPLE: REPETITION

DEEP IN THE WOODS

Written by Julie Fogliano

Illustrated by Lane Smith

At the top of a hill

sits the house that is leaning.

A house that once wasn’t

but now it is peeling.

A house that was once - painted blue.

Tiptoe creep

up the path

up the path that is hiding.

A path that once welcomed.

A path that is winding.

A path that’s now covered in weeds.

Repetition is a word or image, or phrase used multiple times in a text.

Here are some examples:

-